The Crew

The Admiralty selected a mix of experience and youthful ambition to lead the 1845 expedition. While the crews of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror consisted of 129 men, the legacy of the voyage is inextricably tied to its commanding officers.

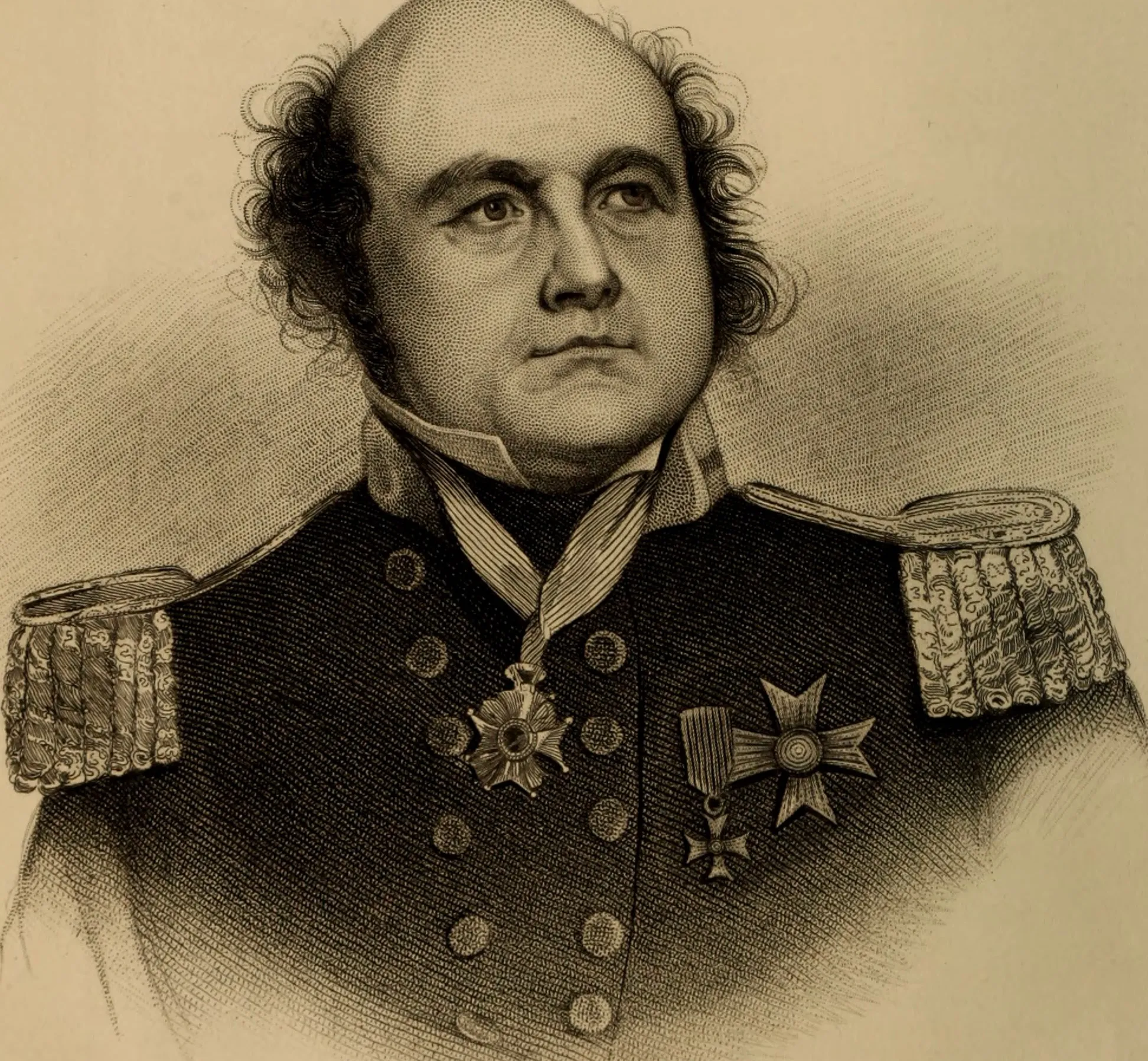

Sir John Franklin (HMS Erebus)

The expedition leader. A career naval officer who rose from a 14-year-old midshipman to a knighted explorer and colonial governor.

Sir John Franklin was a veteran naval officer whose career spanned the Napoleonic Wars and the pioneering era of Arctic discovery. He joined the Royal Navy at the age of fourteen and saw action in major fleet engagements, including the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. His early interest in exploration was cemented during the first successful charting of the Australian coastline, a mission that shifted his focus from military combat toward the expanding frontiers of global maritime science.

Franklin became a prominent figure in British exploration following two extensive overland surveys of the Canadian North. During his first journey (1819-1822), his team famously survived extreme starvation by eating boiled leather from their own boots, earning him the legendary nickname “the man who ate his boots.” He later commanded a highly successful second expedition between 1825 and 1827, where he utilized more self-sufficient logistical planning to map nearly 2,000 kilometers of previously unknown Arctic coastline. Passing through Upper Canada on his return journey in August 1827, Franklin stopped at a small lumber community called Bytown, which later became Ottawa, Canada’s capital.

Before his final voyage, Franklin served in a high-profile civilian capacity as the Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (modern-day Tasmania). In 1845, at the age of 58, he was appointed overall commander of the most ambitious Northwest Passage expedition in history. As the leader of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, he was regarded by his crew as a strongly religious and interesting officer who often shared stories of his earlier adventures over dinner in his cabin, providing a steadying presence for the 129 men under his command.

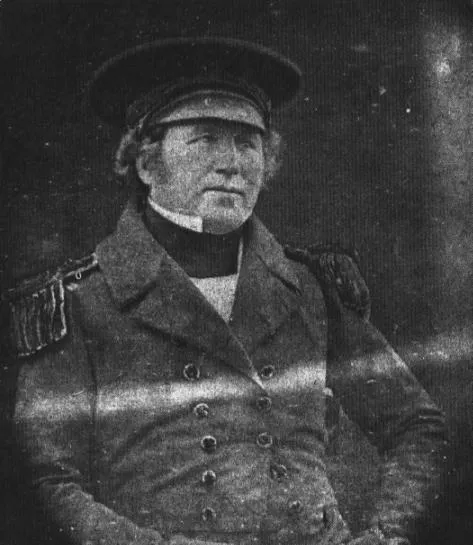

Captain Francis Crozier (HMS Terror)

Francis Crozier was an Irish naval officer and scientist who served on the HMS Terror as the second-in-command of the 1845 expedition. By the time he joined Franklin, Crozier had already participated in several major polar voyages, including multiple attempts to navigate the Northwest Passage and a renowned four-year scientific mission to Antarctica. His expertise in terrestrial magnetism was so significant that it earned him a fellowship in the Royal Society.

While Sir John Franklin held overall leadership, Crozier was the captain of the HMS Terror and was primarily responsible for the expedition’s survival after Franklin’s death in June 1847. It was Crozier who made the final, desperate decision to abandon the ice-locked ships in April 1848 and lead the remaining 105 survivors on an overland trek south toward the Back River. His leadership during these final months is documented in the Victory Point note, and his movements were preserved through the oral traditions of the Inuit who witnessed the crew’s progress.

Commander James Fitzjames (HMS Erebus):

James Fitzjames was a distinguished Royal Navy officer whose career was defined by technical expertise and notable bravery. Born as the illegitimate son of Sir James Gambier, he was raised by the well-connected Coningham family, who provided him with an exceptional education. Fitzjames rose rapidly through the naval ranks, earning a reputation for daring exploits during the Euphrates Expedition in Mesopotamia and his service as a gunnery lieutenant in the First Opium War.

In 1845, Fitzjames was appointed Captain of the HMS Erebus. Beyond his duties as a captain, he was given the critical responsibility of recruiting the expedition’s personnel, selecting many of the officers and sailors who would fill the fleet’s ranks. Within the ships, Fitzjames was viewed as an officer—energetic, highly qualified in gunnery science, and a popular leader who provided a vital link between the senior commanders and the rest of the crew.

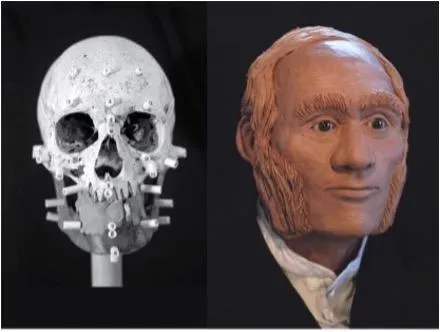

John Gregory (HMS Erebus)

John Gregory was a specialist engineer from Salford, Lancashire. Unlike the career naval officers, Gregory was a railway engineer by trade, employed by Maudslay, Sons & Field. He was recruited specifically because the expedition’s ships had been outfitted with converted locomotive engines to provide auxiliary steam power—a revolutionary but unproven technology for Arctic exploration.

Though he had never been to sea before 1845, Gregory served as a warrant officer on the HMS Erebus, reporting directly to the captain. He survived the three years the ships spent trapped in the ice and was part of the final group that deserted the vessels in April 1848. He eventually perished at Erebus Bay during the desperate march toward the Canadian mainland.

In 2021, his remains became the first of the entire 129-man expedition to be positively identified through DNA analysis, linking him to his great-great-great-grandson in South Africa.

Interactive Evidence: The Victory Point Note

The “Victory Point Note” is the only written record recovered from the expedition. It tells a story of two different times: optimism in 1847, and catastrophe in 1848.

Instructions: Slide to compare the standard Admiralty form with the scribbled margins added by Crozier and Fitzjames on April 25, 1848, confirming Franklin’s death and the desertion of the ships.

The Mission Next up:

Inuit Knowledge & Rediscovery

Bibliography

- Government of Canada. (2022). Who's who in the Franklin expedition. In Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://parks.canada.ca/lhn-nhs/nu/epaveswrecks/culture/histoire-history/qui-who

- Government of Canada. (2018). Sir John Franklin. In Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sir-john-franklin

- James H. Marsh, Owen Beattie, Tabitha de Bruin. (2018). Franklin search. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/franklin-search

- Wikisource contributors. (2026). A Naval Biographical Dictionary/Crozier, Francis Rawdon Moira. In Wikisource. Retrieved from https://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=A_Naval_Biographical_Dictionary/Crozier,_Francis_Rawdon_Moira&oldid=11665383

- Geraldine Rahmani. (2006). Francis Crozier (1796-1848?). In Arctic. Retrieved from https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/arctic/article/view/65219

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025). James Fitzjames. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=James_Fitzjames&oldid=1329988743

- Douglas R. Stenton, Stephen Fratpietro, Robert W. Park,. (2024). Identification of a senior officer from Sir John Franklin’s Northwest Passage expedition. In Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 59. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352409X24003766